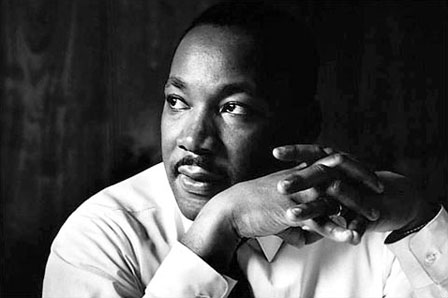

MLK And Why I Write About Spirituality

![]()

![]()

![]()

Surprisingly, through all the talk about MLK we've heard today, there's one aspect of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. we aren't hearing that much about: the fact that he was a Christian.

Yes, believe it or not, he had that "Dr." at the beginning of his name because he had a doctorate in theology. Yes, he spent some time leading civil rights protests, but he spent much more time being a preacher.

Okay, maybe you knew that part. But what we really don't hear about often is that King's Christianity was rooted in his personal spiritual experience.

When discussing his spirituality, people usually say King was influenced by Christ's or Gandhi's "philosophy" -- as if, based on a sober assessment of their logic and evidence, King concluded their ideas were sound -- but they don't touch on what King saw as his firsthand encounter with the divine.

MLK's Epiphany

I've read and listened to a lot about King, but I only recently heard this story. One night in 1956, King's struggle was taking its toll, and he was feeling tired and defeated. Sitting at his kitchen table, he started praying out loud. Suddenly, he "experienced the presence of the Divine as I had never experienced Him before."

"It seemed as though," he wrote in Stride Toward Freedom, "I could hear the quiet assurance of an inner voice saying: 'Stand up for righteousness, stand up for truth; and God will be at your side forever.' Almost at once my fears began to go. My uncertainty disappeared. I was ready to face anything." This experience convinced him to stay on his course, and become the leader he became.

When reading about this event, it struck me that this would be a great story to tell the people I know and read who scoff at spiritual practice, and say it's a waste of time. "Why spend all that time meditating or praying? Why not go out and do some good in the real world?" they ask.

Some Crazy Ideas

Here's a controversial thought: what if the very idea of "goodness" has its roots in spiritual experiences like King's? In other words, what if we wouldn't even have any sense of what it means to "do good," without the guidance of people who have had personal encounters with divinity?

The founders of the great religious traditions -- Jesus, Buddha, Muhammad, and so on -- are all said to have had life-changing shifts in their consciousness that convinced them of their calling. These figures' spiritual experiences inspired the teachings and behavior they brought into the world, which in turn created much of what we now call "morality" and "ethics." At least, so some say.

And how about another crazy idea: what if the very purpose of spiritual practice -- meditation, prayer, chanting, and so on -- is to bring about that same state of consciousness? To give the everyday person access to the compassion, inner strength, and sense of universal interconnectedness that drove people like King to accomplish what they did?

If spiritual practice can do that for us -- and, in the interest of full disclosure, I believe it can -- I think it's actually one of the best uses we can make of our time.

Why Growth Is Good: New Free E-Book

I'm pleased to introduce you to a collection of articles from this site that I've put together called "Why Growth Is Good: The Case for Personal Growth, Self-Help and the 'New Age'," which is available here as a free e-book. I've edited many of my posts together into longer essays, and I've also written a new introduction.

These essays have the same goal as this site -- to present a compelling, organized argument for the value of personal development ideas and practices, and respond to their critics.

This book will be great food for thought if you've ever wondered about any of these questions:

* Are there practical benefits to self-development practices like meditation, yoga, and transformational workshops?

* Does self-help advice that encourages taking personal responsibility invite us to beat ourselves up?

* Does the same kind of advice discourage us from caring about others?

* Is psychotherapy about nothing more than whining about our families of origin?

* Did too much "positive thinking" cause the recent economic downturn?

* Do people who are into self-help tend to be more selfish and less generous?

* Is there a danger that self-development practices may make us feel "too happy" and neglect problem areas in our lives?

* Do personal development ideas discourage us from getting involved in politics?

I hope you enjoy this compilation, and I'm looking forward to your feedback!

(Sponsored by http://e-library.)

Growth As An Opiate, Part 5: Self-Development And The “War On Envy”

The idea that societies with more economic inequality -- whether in terms of income, net worth, or something else -- are less moral is nothing new.

In the past, people have usually made this argument from a philosophical perspective -- for instance, John Rawls' famous argument that, if you designed a society from scratch, with no idea where you personally would end up on the economic scale, you'd choose a society where inequalities were only allowed if they benefited the worst-off.

Today, however, people are increasingly making this argument in psychological terms. The larger the economic inequalities in a society, advocates of this view argue, the more emotional distress and "lack of social trust" -- i.e., envy -- people will feel.

For example, in The Spirit Level, a book Evan pointed out to me, epidemiologists Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson claim that societies with more wealth inequality, and therefore more (if you will) envy per capita, tend to suffer from lower lifespans, more teenage pregnancy, and a host of other problems. Not surprisingly, Pickett and Wilkinson argue that -- at least, in already rich countries -- more wealth redistribution will create a healthier and happier population.

Thinking about this argument raises two interesting questions for me. First, even assuming envy creates social ills, is designing government policy with the goal of reducing envy a good idea? Second, are there other ways to reduce society-wide envy that don't involve the use of state power?

Mission Creep In The "War On Envy"

I'll admit, the argument that the government should act to combat envy is disturbing to me. One reason is that, although The Spirit Level and similar books focus on envy created by inequalities of wealth, there are obviously many other forms of inequality that cause jealousy.

For example, suppose I resent what I see as your biological superiority -- maybe you're taller and have lost less hair than me. Or perhaps I'm jealous of your relationships -- maybe you're married to the woman of my dreams, and I wish she were with me.

If money-related envy causes social ills, I'd wager that other types of envy have similar effects. In other words, if wishing I were as rich as you renders me more susceptible to disease and shortens my lifespan, surely "wishing I had Jessie's girl," or that I had somebody else's athletic talent, will also be debilitating.

You can probably tell where I'm going. Does this mean the government should engage in "sexual redistribution," and compel attractive people (by whatever measure) to accept intimate partners they wouldn't otherwise choose? Should we adopt Harrison Bergeron-style rules requiring, say, people with natural athletic ability to wear weights on their legs?

In other words, if we're willing to redistribute wealth in the name of fighting a "War on Envy," it's hard to see why social policy shouldn't reach into other areas of our lives in ways most people -- regardless of political persuasion -- would find repugnant.

Does Self-Development Soothe Envy?

Earlier in this series, I discussed critics of personal development who cast it as a sort of modern-day "opiate of the masses." These critics argue that practices like psychotherapy, meditation, and affirmations, precisely because they're geared toward relieving human suffering, are socially harmful.

Why? Because, these authors say, the main source of human angst in modern times is economic inequality. At best, self-development practices only offer a temporary "high," because they don't attack the root of this problem. At worst, these practices perpetuate injustice, because -- like "cultural Prozac" -- they distract the masses from the inequality-induced suffering that would otherwise spur them to rise up against an immoral capitalist system.

What if we took this critique at face value for a moment, and assumed that self-development does reduce some of the pain caused by envy? In other words, what if meditating, saying affirmations, or doing similar practices actually can cause people to feel less jealous of others? In my own experience, this has some truth to it -- the more I've kept up my meditation practice, the less I've found myself unfavorably comparing myself to others.

Perhaps the widespread adoption of these practices would make people less interested in redistributing wealth. But if that's true, in all likelihood, these practices would also lessen people's tendency to suffer over other kinds of inequality -- envy about other people's intimate relationships, jealousy over others' looks and natural aptitudes, and so on.

So, if we take Pickett and Wilkinson at their word, and assume envy causes all kinds of social ills, it stands to reason that personal development -- at least, the types of self-development with real emotional benefits -- may help create a happier and healthier society. On balance, maybe a little "cultural Prozac" isn't such a terrible thing after all.

Other Posts in this Series:

The Circumcision Ban And The New Atheism

You've probably heard about a recent campaign in San Francisco, California to put a measure on the ballot banning circumcision. I think this campaign illustrates some of the troubling assumptions people are increasingly making about spirituality in our culture, and I'm going to look at some of those assumptions in this post.

Lloyd Schofield, who started the campaign, explains the ban by saying that "it's a man's body, and his body doesn't belong to his culture, his government, his religion or even his parents." Thus, according to Schofield, forcibly removing a male baby's foreskin is immoral.

Religion Isn't Like A Nose Job

This argument may sound good on the surface, but if we examine it more closely, we can see that it proves too much. What about situations where surgery is required to save an infant's life? Should such operations be banned because "it's the infant's body" and no one has the right to invade it? I think most people would say no.

But this, I'm sure Schofield would respond, doesn't undermine the ban, because circumcision is never (as far as I know) needed to save babies' lives. Instead, he has said, it's more like "cosmetic surgery." No one should be forced to get a facelift, the argument goes, and the same principle applies here.

The trouble with this argument is that, for many, if not most, of the people who choose to have their babies circumcised, the procedure is not akin to cosmetic surgery at all. It's a religious requirement. If you believed, as these people do, that God exists, He is the ultimate arbiter of morality, and He wants you to circumcise your child, I don't think you'd see it as a trivial matter.

In other words, when we unpack the rationale for the circumcision ban a bit, we can see that it's based on an idea hostile to religion: that religious practices are just as frivolous and unnecessary as cosmetic surgery.

If we want to have an honest debate about this law, I think we need to acknowledge that it's based on anti-religious assumptions of the sort we often see in the writings of "New Atheists" like Christopher Hitchens and Sam Harris, and ask the ban's proponents to justify those assumptions.

The False "Religion Vs. Morality" Distinction

But there's a deeper, and more problematic, assumption behind the ban -- the notion that the ban is justified by moral principles that are separate from, and superior to, religious beliefs. "People can practice whatever religion they want, but your religious practice ends with someone else's body," says Schofield.

Again, this sounds convincing at first, but let's take a closer look. Where do the ban's defenders get the moral rule that "your religious practice ends with someone else's body?"

Did they learn this through scientific observation? No. As philosophers have often pointed out, moral principles are different from laws of nature like the law of gravity -- we can't learn what's right and wrong by conducting experiments.

Some might argue that Schofield is expressing moral values most people share. However, even assuming most people buy the principle that "your religious practice ends with someone else's body," that doesn't make the principle true. To use a timeworn argumentum ad Hitlerum, a majority of the German people may have supported Hitler's rise to power, but I think you'd agree that doesn't mean it was a good thing.

My point is: it's far from obvious that the principle "your religious practice ends with someone else's body" is somehow more valid than the religious view "God commands me to circumcise my child." Neither principle is more "neutral" than the other, and there's no good reason to dismiss the second one just because it contains the word "God."

I suspect we'll see more and more legislation influenced by "New Atheist" ideas being proposed, and I think we need to understand those ideas and the role they're playing if we want to have a fully informed discussion about these laws.

Rhonda Byrne’s The Power: Is The Packaging The Problem?

A common reason people attack The Secret (and now, Rhonda Byrne's sequel, The Power) is that it promotes a self-centered and "consumerist" attitude. Byrne, critics say, encourages us to focus on "manifesting" luxury cars, expensive shoes, and so on, rather than on helping others.

It's true that the Law of Attraction is often packaged as something we can use to improve our own lives, rather than those of others. The publisher's description of The Power, for example, proclaims that "perfect health, incredible relationships, a career you love, a life filled with happiness, and the money you need to be, do, and have everything you want, all come from The Power."

On the other hand, we can certainly imagine people using the Law of Attraction (assuming, for the moment, that it works) to serve others. Perhaps we might visualize a sick relative getting better, hungry people receiving food, or a dangerous tropical storm abating -- just as Buddhists pray for the wellness of all beings in Metta, or loving kindness, meditation.

So, I suspect many critics' real gripe with the Law of Attraction has to do with the "self-centered" way they think it's marketed, rather than the concept itself.

The "Opportunity Cost" of Spirituality

To be sure, some critics recognize that the Law of Attraction -- again, assuming it works -- can potentially be used to help others. The real problem, they say, is that it obviously doesn't work. Wishing a tropical storm won't devastate a town simply won't have any effect.

Even if this critique is right, I think it's open to the objection "so what?" People do all kinds of pointless activities, such as (in my opinion) watching reality TV and tweeting about what they ate for breakfast. Even assuming it accomplishes nothing, why is visualizing the improvement of others' lives more problematic?

This is where some charge that trying to "manifest" what we want isn't just a waste of time -- it's socially harmful, because every minute we spend visualizing is a minute we could have used taking concrete action to help somebody.

Interestingly, this is the same objection we often see critics of "mainstream religion" making. People who pray to God to relieve suffering in the world are misguided, the critics say, because there is no God. But more importantly, churchgoers are squandering time they could be spending on real charitable work. (This is the sort of thing we often hear from "New Atheist" Sam Harris.)

Religious People Give More

If this argument is right, we should expect religious people to do less charitable giving than unbelievers. While believers are uselessly propitiating their imaginary sky-god, atheists are down in the trenches, solving real people's problems -- right?

Actually, much evidence suggests the opposite: religious people tend to be more generous than unbelievers. In Who Really Cares, a study of charitable donation, economist Arthur C. Brooks found that religious belief was the strongest predictor of giving to charity among the factors he looked at -- more so than any political orientation, age group or race.

So, while it may be true that believers spend time in worship that nonbelievers don't, it seems religious people nonetheless find the time to do more giving. But why?

One plausible explanation I've heard is that religious people are happier. They feel more secure, and grateful, living in a universe they see as orderly and benevolent. And psychological studies have found that happier people tend to give more generously.

In any case, all this suggests that we shouldn't be too quick to conclude that adherents of the Law of Attraction are less likely to be charitable, simply because they believe their thoughts can affect reality. Of course, because the ideas in The Secret are different in many ways from traditional religion, we shouldn't necessarily assume The Secret's followers are more giving either.

We'll explore this issue in more depth soon.

Personal Development Politics, Part 2: The Elections and Self-Responsibility

We've been looking at the argument, made by some personal growth critics (Salerno posted about this, for example), that self-development's emphasis on personal responsibility favors political conservatism. If this is true, I've been asking, why do self-development teachers tend to be politically liberal? Is it because they don't see the implications of their ideas?

Like I said in my last post, I think the answer is no. I've seen many examples of personal growth teachers consciously embracing both liberal politics and a belief in human beings' ability to control their circumstances.

This recent Huffington Post piece by meditation teachers Ed and Deb Shapiro is a good illustration. The Shapiros don't seem particularly thrilled about the recent U.S. election — they describe it as characterized by “weird and unqualified people vying for top government positions," by which they presumably mean some of the Republicans who swept the House of Representatives.

At first, the Shapiros may sound like they're counseling people who are upset about the elections to give up, and accept that there's nothing they can do to change the situation. "It is our ability to be fully present and engaged that enables us to accept every situation exactly as it is," they write, inviting us "to embrace difficulties, deep sadness, upset feelings, or injustice while staying aware, present, and available."

Self-Responsibility and Social Change

However, the Shapiros go on to reveal a strong, perhaps even radical, belief in personal responsibility. We can only work for social change, they explain, when we drop our griping about the situation, "for in that moment of acceptance we can move to transform it."

Once we fully accept what's true right now, the power of our thoughts and actions to change the world is at its height. "Everything we think, say, and do has an immediate effect on everyone and everything else," they write, and this "means that we have enormous resources available to us at all times."

In other words, although they stop short of embracing a full-blown "Law of Attraction," and saying we can conjure up things we want through thought, the Shapiros clearly are firm believers in individuals' ability to shape their situation, and reject the Marxian notion that we're basically pawns of impersonal social forces.

Also, notice that the Shapiros' belief in self-responsibility doesn't lead them to reject politics as a means of solving social problems -- their whole piece, though abstract, is about how adopting an attitude of mindful acceptance can actually empower people to reverse the current political trend.

But What About "Blaming The Victim"?

I can imagine a critic arguing that, although the Shapiros may think it's consistent to be politically liberal and believe in radical self-responsibility, they're simply wrong.

This is because, the argument goes, a major tenet of political liberalism is that the government should create a fair society by redistributing wealth. This, in turn, is based on the notion that each person's wealth is mostly a matter of luck -- how much they inherited, their genetic makeup, and so on.

However, the belief that we can create our circumstances implies that we're responsible for how wealthy we are. If we're poor, that can't be due to bad luck -- it must be because we're lazy. And if we're lazy, that means we don't deserve to have wealth redistributed in our favor.

As I've touched on briefly before, I disagree. I don't think you need to believe that everyone's circumstances are solely, or even mostly, the result of chance to consistently be a political liberal, as I've defined it.

I'll list four reasons why below. (Notice how the arguments I'll make can also be used to justify voluntary charity, if government redistribution of wealth isn't your thing.)

1. Social Harmony. Some, like this organization that Evan pointed out, argue that societies with lower disparities in wealth are more harmonious, in that their people tend to live longer, they have fewer violent crimes and less teen pregnancy, and so on.

I haven't looked in detail at their evidence, so I'm agnostic about what they say, but the point is that it can be used to justify economic equality regardless of whether the less well-off "deserve" contributions from the better-off.

To illustrate, if I was certain that giving money to someone in poverty would extend my lifespan by five years, I'd probably do it regardless of whether he was responsible for being poor.

2. Compassion for people who make bad choices. Suppose your friend became a drug addict and, as a result, lost his job. Would you feel no compassion for him, and refuse him help, because he chose to use drugs? I don't think you would. In other words, it's certainly possible to feel compassion for people whose predicament is arguably "their own fault."

3. The "Unconscious Beliefs" argument. It may be the case that (1) we're all totally, or mostly, responsible for the situation we find ourselves in, but (2) not everybody knows that.

For example, suppose I harbor the unconscious belief that "I deserve to suffer and be poor." I'm "responsible" for this belief, in the sense that it exists in my own mind, but I may not be conscious of its existence or my power to change it. Many self-development teachers (T. Harv Eker is a popular example when it comes to money) see it as their role to make people aware of "limiting beliefs" like these.

What's more, one might argue, so long as there are people who aren't conscious of their ability to control their economic circumstances, redistribution of wealth or private charity is sometimes needed to help such people.

4. Divine Command. As you know, many people believe that God, or another supernatural force, has given them an unqualified command to be charitable. From these people's perspective, it's our job to help the less well-off, regardless of whether they're "at fault" for their plight.

What do you think? Is a strong belief in personal responsibility inherently conservative?

NPR and the Social Stigma Around Psychotherapy

Politics aficionados among you have probably heard about National Public Radio (NPR)'s firing of journalist Juan Williams, over his comment about the anxiety he feels getting on a plane with someone dressed in Muslim garb.

The controversy over Williams' firing didn't interest me as much as the comments by NPR's chief, Vivian Schiller, in the aftermath. In a press conference, Schiller said Williams should have kept his feelings between himself and "his psychiatrist or his publicist."

This stirred up even more controversy, with Williams' supporters blasting Schiller for basically suggesting Williams was mentally ill and in need of a psychiatrist. Schiller apologized, saying her remark was "thoughtless."

This incident illustrates the continuing strength of the stigma, in our culture, around working with a psychotherapist. As near as I can tell, Schiller's comment was just a poorly timed joke -- it wasn't meant to be a factual statement that Williams was seeing a psychiatrist. Nonetheless, people on both sides of the issue took what she said as a serious insult.

Why The Stigma?

Why is it considered insulting in our society to suggest that someone is working with a therapist? My sense is that there are two reasons.

First, the common belief seems to be that people only see therapists if they're "mentally sick," the same way we see a physician if we have the flu. Thus, any public figure who's seeing a therapist must be unfit to do his job or hold office.

Another widespread assumption about therapy is that it's something only weak people do. A strong person, after all, can handle their own psyche and emotions, and doesn't need anyone to help them do it.

Therapy And Humility

I disagree with both of these assumptions. In fact, I'd be more inclined to trust a public figure -- politician, celebrity, or whatever -- who voluntarily sought out a therapist than one who didn't, especially if they were courageous enough to admit it in public.

Why? First off, a person working with a therapist is probably doing so because they understand that they, like all humans, are imperfect and have room to grow. With that understanding, I think, comes humility.

I wouldn't want the country run by someone under the illusion that they had no flaws. A person who believes they can do no wrong, I think, is dangerous in a leadership position, and history is littered with examples.

Therapy And Personal Growth

What's more, I think it actually takes a lot of strength to be willing to see a therapist. If we have the good fortune to find a therapist who's ready to do deep work with us, we're going to visit many aspects of ourselves and our personal histories that aren't at all pleasant.

Also, a skilled therapist can help us see "blind spots" in how we relate to the world that we, and people we surround ourselves with, aren't aware of. Unless someone helps us get conscious of them, our lifelong patterns of people-pleasing, manipulating others, defending ourselves from childhood threats, and so on, can run the choices we make without our knowledge. I'd be more likely to trust someone whom I knew had worked to develop this kind of awareness.

And yes, I'm speaking from personal experience. (Oops, there goes my political career!) I've worked with therapists, but not because I saw myself as sick, broken or weak. Self-development junkie that I am, I see psychotherapy -- done skillfully -- as one of the most powerful opportunities for personal growth.

Regulating Self-Help, Part 2: What Is A Benefit?

Last time we saw that, if we wanted to determine whether, and how much, to regulate personal development, we'd need to weigh the costs of self-development activities against their benefits.

This, as I said, raises yet another question: who is qualified to say whether someone benefited from a personal growth practice? In other words, should we trust the subjective opinion of the person who did the activity? Or, should we decide whether they got value based on some set of objective criteria?

For example, if you come back from a meditation retreat and say you got a lot out of it, should we trust your judgment? Or, should we only agree with you if certain objectively measurable facts exist -- for instance, if your heart rate is lower than it was before you went to the retreat; if you've had fewer arguments with your spouse than before; or something along those lines?

Trusting The Consumer

Generally, in Western society, we trust the individual consumer's judgment, and refrain from regulating, where the activity isn't obviously harming any third parties -- even if the activity seems ridiculous or distasteful to many.

For instance, I don't need a permit to listen to Christian Death Metal, and people who play it need not pass a licensing exam. The majority of the population may hate this music, but the government doesn't regulate it, because my listening to it doesn't injure anyone else. (I mean, some take offense at its existence, but the law doesn't usually care about that kind of "injury.")

As I see it, meditation retreats, and other personal development practices that don't obviously hurt third parties, should get the same treatment. Sure, some may think meditation is weird or a waste of time. But those people's distaste alone isn't a good argument for regulation. I think most people will be on board with this, at least.

What Are The Exceptions?

So, the question becomes: when should we depart from this standard? When should we disregard the consumer's judgment, and demand objective proof of the practice's effectiveness? Let's look at a few possibilities critics of personal growth sometimes raise.

1. The Price Is Too High. Like I said earlier, critics often focus on what they see as the exorbitant prices of products, seminars, and so on. One much-discussed example is this ABC News piece about Joe Vitale's offer, for $5,000, to take people for a ride in his Rolls-Royce and teach them how to attract wealth.

I'm deliberately using this example because it seems like a "hard case" -- I wouldn't personally spend $5,000 to do this. But I think we need to look a little deeper to determine whether it's worthy of regulation.

To some, it doesn't matter how many people who take a ride with Vitale might think they got their money's worth. The government should ban this practice, order Vitale to lower his prices, or at least require his customers to show, to the government's satisfaction, that they won't starve if they fork over the $5,000, and they aren't psychologically impaired in some way.

The assumption is that, objectively, there's no way this consultation with Vitale could possibly confer $5,000 worth of benefits, whether financial or emotional. Anyone who thinks otherwise must be delusional or ill-informed.

Should We Crack Down On Vacations?

But let's think for a moment about another thing people often spend lots of money on: vacations. Sad, perhaps, but true: some people spend thousands of dollars to fly their families to an exotic locale, stay in hotels for a week or two, eat out, and go to museums.

Is there an objectively measurable benefit to this? Is there reliable evidence that people make more money, become less likely to get divorced, or have lower heart rates after taking a vacation involving air travel and luxury hotels? (Remember, I mean an expensive vacation of the kind well-paid professionals take, not a "staycation.")

I think the honest answer to one or both questions is no. And yet, nobody suggests psychologically screening people who want to go to the Bahamas. Moreover, at least in the U.S., no license is required to be a travel agent.

In other words, we don't second-guess people's decisions to take expensive vacations, or assume that they couldn't possibly have received enough value from their trip to justify what they paid.

To be sure, if overhead luggage falls on somebody's head in a plane, or they get food poisoning from a hotel restaurant, they can use the tort system, i.e., sue the responsible party. But that's true of Joe Vitale too -- for example, if someone rode in Vitale's limo and it crashed, they could sue him for negligence. Regulation, commonly understood, is different from tort law, in that it tries to prevent harm rather than compensate for it -- through licensing requirements, safety inspections and so forth.

So what's the difference? Is it that Vitale and some other self-development teachers base their approaches on spiritual-sounding or "woo-woo" ideas? I'll open that up for discussion.

Regulating Self-Help, Part 1: Defining Some Terms

I expect that, once James Arthur Ray's manslaughter trial begins, calls to "regulate self-help" will become louder and more widespread. Because there's a lull in media coverage of the Sedona incident, I think now is a good time to soberly consider some questions about whether and how the government could go about regulating personal development, and the impact regulation might have.

I'm going to raise some of those issues in this series. I think the first question to address is what we mean by "regulation," since we can't go into the particulars of what and how to regulate without that understanding.

What Is Regulation?

After all, self-development books, seminars, and so on are already subject to many generally applicable laws -- meaning laws that weren't specifically designed for personal development, but apply to it anyway.

The criminal laws obviously apply to personal growth teachers, as we see in the Sedona matter. Contract and tort law applies to self-development -- if someone sells a book or leads a workshop that doesn't do what its advertising promised, they can be sued for fraud or breach of contract. In this sense, self-development is already "regulated."

But in my experience, this isn't usually what people mean when they talk about regulation. My sense is that "regulation" typically refers to laws and rules tailored to a particular business or area of life -- for example, self-help, or securities trading.

Normally, regulations, as commonly understood, are also preventive -- meaning they require us to take precautions to prevent harm, rather than punishing people for inflicting harm. Laws against driving without a license are a good example -- they don't punish people for causing accidents, but rather for failing to pass tests that, in the state's view, ensure that they will drive with some degree of safety.

Some areas of personal development are "regulated" in this sense. To hold yourself out as a therapist, in most of the U.S., you need a license, and to get that license you need to -- among other things -- earn an advanced degree in psychology and pass a test. Other areas are not. For example, I (thankfully) don't need a license to be a self-development blogger.

The Need For Cost-Benefit Analysis

So, the next important question, in my view, is: do we need more regulations of the preventive sort in the self-development field? To answer that question, we need some idea of the costs and benefits of personal growth ideas and techniques.

I think this is a key point, because the criticisms and calls for regulation around personal development tend to focus solely on its costs. But that discussion is incomplete. For example, we often hear people decry the outrageous price of a product or workshop. But without an understanding of that offering's benefits, we can't fairly judge whether its price is "too high."

A new car in the U.S. typically costs tens of thousands of dollars, which to most people seems like "a lot of money" in the abstract, but people are often willing to pay that kind of price for a car because of the benefits they expect from car ownership -- being able to go various places quickly, and so on.

Importantly, as a society, we regularly do this kind of cost-benefit analysis even when it comes to activities involving a risk of serious injury or death. To go back to an earlier example, driving is obviously this kind of activity.

If we only looked at the number of deaths and injuries that happen while driving, we would instantly decide that a total ban on driving was justified. But that hasn't happened, because the benefits of being able to drive are widely recognized.

Hold On, What's A Benefit?

This brings us to yet another series of questions: what are the benefits of personal development? What qualifies as a "benefit"? Who gets to make that judgment?

For instance, if someone subjectively reports that they "feel better" due to some personal growth practice, does that mean they benefited from it? Or will we require a "benefit" to be objectively measurable -- for instance, will we judge a product or service as worthwhile only if people who use it tend to make more money, "find the one," or something along those lines?

All this and more . . . coming soon!